- Proudfoot Post

- Posts

- Nasturtium From The Andes to Europe

Nasturtium From The Andes to Europe

Nasturtiums origins - Interesting facts - Poor man’s capers

🌺 My Deep Dive into Nasturtium (Tropaeolum sp.)

Before we enter the plant lore, let me introduce you to our peppery little friend: the nasturtium. Flamebourn, edible, and resilient, nasturtiums (Tropaeolum spp.) are some of the most prolific plants I’ve had the pleasure of growing and working with.

In this exploration, I’ll walk you through nasturtium’s origins and native ecosystem, how it was embraced (and transformed) by European culture, and finally, how to make one of my favourite foraged condiments: nasturtium “capers” a poor capers.

Let’s begin.

From the days it sprawled across the outcrops and stone walls of the Andes.

A wild ember in the highlands.

Hands and breath of South American tribes medicine and memory in every petal.

It crossed the ocean, cultivating itself into European lore a symbol of valour and of patriotism.

It shows colour to me when colour fades a firework of feast for creatures with wings.

It casts a gentle blanket across my forest floor

offering me leaf, flower and seed.

🌿 Tropaeolum: From Andean Earth to European Gardens

🌄Origin:

Nasturtiums are native to the mountainous regions of Central and South America, particularly the Andes, where they grow in high-altitude cloud forests and rocky slopes. These rugged environments, with thin soils, intense sunlight, and cool nights, shaped nasturtiums into resilient, sun-loving plants. For nasturtium to survive these conditions it has evolved to climb, trail and sprawl. Although its ability to grow ‘wildly’, it never seems to smother other plants within my food forest, i can see it in my mind living amongst Andean crops and wild medicinal plants, forming part of a rich, diverse landscape managed by Indigenous communities for generations. I believe that this plants ability to successfully thrive in harsh conditions has led to its widespread cultivation around the world.

🍠 Tropaeolum tuberosum (Mashua):

Tropaeolum tuberosum, known across the Andes as mashua, is a brand new one for me and oh boy! it’s fascinating. Similar to that of common nasturtium yet it has tubers similar that of potato. Mashua has been a staple food for Andean communities for millennia. Rich in carbohydrates, vitamin C. and even libido-suppressing properties. In fact, Inca rulers were said to issue mashua as a dietary control for soldiers. A fascinating intersection of botany and indigenous knowledge.

🏛 European Garden

Nasturtiums arrived in Europe in the late 1500s, brought by Spanish explorers and naturalists who had begun cataloguing New World plants. At first, it was Tropaeolum majus the round-leaved, vividly blooming nasturtium that caught Europe’s eye. It wasn’t grown for its food value right away, but for its striking beauty and unusual appearance.

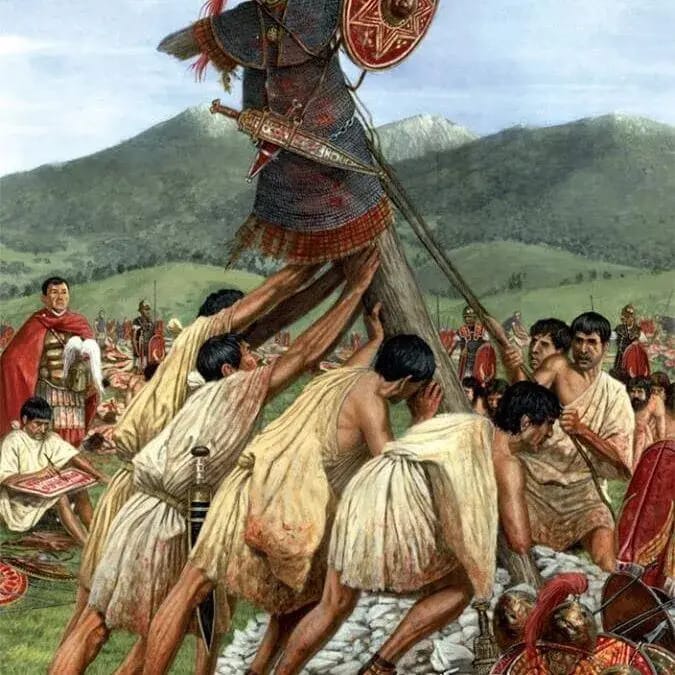

Carl Linnaeus named the plant Tropaeolum, from the Latin tropaeum a word used for trophies taken in battle. The leaves resembled shields; the flowers, blood stained helmets.

Over time, European herbalists began to explore nasturtium’s medicinal uses. It was found to have antiseptic, expectorant, and diuretic properties. It became a remedy for chest congestion, urinary infections, and even scurvy, thanks to its high vitamin C content.

In European folk magic and symbolism, nasturtiums came to represent courage, protection, and triumph.

By the Victorian period, nasturtiums were everywhere climbing trellises, spilling over stone walls, and popping up in kitchen gardens as both medicine and food. Their easy cultivation and cheerful appearance made them a garden classic, especially beloved in cottage and herb gardens.

Interesting cultivars:

Alaska Series  Blue Nasturtium |  Whirlybird Series  Hermine Grashoff |

Poor Man’s Capers: A Fermentation Ritual

One of the simplest and most satisfying ways to work with nasturtiums is in the kitchen. Every part of the plant is edible—leaves, flowers, and especially unripe green seed pods. When pickled, these seeds become a tangy, peppery substitute for capers. Historically, they’ve been known as “poor man’s capers”, and they’re surprisingly easy to make.

How to Make Nasturtium Capers:

Ingredients

1 cup fresh, green nasturtium seed pods (young and tender)

1 tablespoon salt

¾ cup vinegar (apple cider or white wine vinegar work well)

Optional: mustard seeds, garlic, peppercorns, dill, or bay leaf for flavour

Instructions:

Rinse the nasturtium seed pods gently and pat them dry.

In a small pot, bring the vinegar and salt to a boil, stirring until the salt dissolves.

Place the seed pods into a clean glass jar with your optional others.

Carefully pour the hot vinegar brine over the pods, making sure they’re fully submerged.

Let the jar cool to room temperature, then seal it with a lid.

Store the jar in the refrigerator and let it sit for at least 1 week before tasting. The flavour will develop over time.

Use your nasturtium capers just like regular capers, salads, fish or sandwiches!

Final thoughts.

This plant is giving! I welcome it on the land, it plays a special role throughout the winter. Nasturtiums is an example of bridging worlds. From the sacred fields of the Andes to the neatly trimmed gardens of Europe, they’ve travelled quietly, bringing with them a story.

They grow fast. They bloom boldly. They’re never fussy, never demanding and yet they offer so much. Whether you plant them for beauty, for pollinators, for medicine, or for your plate, nasturtiums remind us that plants carry wisdom, and often the richest tales.

I hope this deep dive leaves you feeling inspired, grounded, and maybe ready to pickle a pod or two.

Below is a scrapbook I did about nasturtium and a Youtube Video too.

|  |